“WYSIWYG: The Films of Michael Snow.” Complete retrospective. January to December 2015

WYSIWYG: The Films of Michael Snow

Twelve monthly screenings throughout 2015. Michael Snow in person.

“At first glance, Snow’s work looks formalist, but the basis is usually conceptual. (His motto might be William Carlos Williams’ ‘No ideas but in things.’) At the same time, his strongest pieces are perceptual. What you see is what you get.” —J. Hoberman

While Jim Hoberman made the above observation in regards to Michael Snow’s photographic practice (on the occasion of the artist’s recent photography show at the Philadelphia Art Museum), the same sentiment could be applied to Snow’s work in the cinema. Snow’s films could easily be described as “things,” their forms so often deriving from the functions they perform: in Wavelength, a camera zoom across a New York City loft ends on a photograph of the sea; See You Later – Au Revoir comprises a slow-motion shot of a man leaving an office; while the titles of Dripping Water and the cryptogrammic <–> (a.k.a. Back and Forth) are sufficient unto themselves to describe their contents. Description, however, pales before the powerful phenomenological experience of the films: as P. Adams Sitney aptly notes, Snow’s central strength is the “discovery of a simple situation permeated by a rich field of philosophical implications which duration elaborates.”

We are thrilled to present this complete retrospective of the film works of Canadian avant-garde great Michael Snow , screening in monthly installments throughout 2015 with the artist in attendance for most screenings. By the time Snow came to filmmaking he was already an artistic polymath, being both an accomplished musician and visual artist. (In fact, his continuing importance in these other fields overshadows his cinema career for many in those communities.) He made his first film, A to Z, in 1956 (working after hours in future Yellow Submarine director George Dunning’s Toronto-based animation studio), but it was not until he and his wife Joyce Wieland moved to New York City in the early sixties that Snow adopted filmmaking as the third term in his trifecta of creative pursuits. Already at the epicentre of NYC’s exploding visual arts scene and hosts to an exciting music scene—the pair were neighbours to the likes of Carl Andre and Frank Stella, while Cecil Taylor, Roswell Rudd and others regularly played in their Soho loft— Snow and Wieland were introduced to the emergent New American Cinema movement when fellow Toronto expat Bob Cowan arranged a private screening of George and Mike Kuchar’s Regular-8 film A Town Called Tempest.

While Snow claims that the Kuchar aesthetic was more in line with Wieland’s interests rather than his own, he was inspired by the twenty-year-old twins’ ability to just go out and make things. Eagerly embracing the possibilities of non-industrial filmmaking, Snow made half a dozen films during his years in New York. The pinnacle achievement of this period was Wavelength, which Snow finished just in time to screen at the fabled EXPRMNTL festival in Knokke- Le-Zoute, Belgium. The film took the festival’s top prize and quickly became recognized as a canonical work of the international avant-garde, and a key text in what soon became known as structural filmmaking.

From Wavelength’s hypnotic linearity to the visceral intensity of <–> and La Région Centrale to the headiness of Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen, it is striking to witness Snow’s ability to seize upon an idea and draw, tease, or wring out its myriad implications and permutations. Also striking is the sheer sonic and visual pleasure of his films, with Snow’s cross-disciplinary interests in music and the visual arts enriching his work in the cinema; and a persistent undercurrent of humour that can range from dryly witty to pure slapstick. Marrying rigorous thought with exhilarating audiovisual trickery, the films of Michael Snow continually force us to question if what we get is really what we see.—Chris Kennedy

Snow in Vienna dir. Laurie Kwasnik | Canada 2012 | 34 min.video

Wavelength dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1967 | 45 min. 16mm

A groundbreaking film that Manny Farber presciently dubbed “a pure, tough forty-five minutes that may become the Birth of a Nation of Underground films” and that Annette Michelson once described as a metaphor for consciousness, Michael Snow’s Wavelength consists of a single, fitful zoom across his New York loft space. Over the course of the film’s duration, furniture movers deliver a shelf, a man breaks into the loft and dies, and a woman discovers the body—all while the zoom continues relentlessly on. The zoom’s compression of time and space serves as a through- line which Snow adorns with a series of techniques—colour filters, a sine-wave glissando, varied film stocks, superimposition, the aforementioned human drama—that distort our perceptions, interrogate the role of narrative in cinema, and execute a radical and transcendental break with the conventions of film language.

A chapter from a long-form documentary project called Fields of Snow that director Laurie Kwasnik has been producing about Snow’s music, Snow in Vienna documents a rare solo piano concert Snow gave at the Wiener Konzerthaus in 2012, a performance that the prolific musician is particularly proud of.

Saturday, January 31 1:00pm

New York Eye and Ear Control dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1964 | 34 min. | 14A 16mm

Reverberlin dir. Michael Snow | Canada 2006 | 55 min. | 14A video

Snow’s first long film, New York Eye and Ear Control is the summa of The Walking Woman, a series that Snow had worked on since 1961. Cutting a piece of cardboard into the shape of a female silhouette, Snow turned it into a type of stencil that he repeated in paintings and sculptures, using it to explore seriality, positive and negative space, and the ways in which a shape can change its surroundings. Deciding to document the effect that cutouts of The Walking Woman had on landscape, Snow positioned his outlines and filmed the results in black and white, creating a vivid collision of two-dimensional form and three-dimensional space. Snow then asked a sextet of the free jazz musicians who occasionally played in his New York loft—Albert Ayler, Garry Peacock, Sunny Murray, Don Cherry, John Tchicai and Roswell Rudd—to record a soundtrack for the film, and the resulting recording serves as a striking counterpoint to the formal order of the images, yet another dichotomy in a film full of dualities and comparisons. (The soundtrack had a second life of its own: released separately on cult label ESP-Disk, it became a free jazz touchstone to rank alongside Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz and John Coltrane’s Ascension.)

After his return to Toronto from New York in the mid-1970s, Snow’s ongoing interest in free music led him to co-found the improvised music collective CCMC, a project which has continued for the last forty years (a long stretch of which included weekly concerts at the many incarnations of the Music Gallery). In Reverberlin, Snow takes the audio of a 2002 performance by CCMC (featuring Snow on piano, John Oswald on saxophone and Paul Dutton on vocals) and marries it with a visual collage of performance footage by manipulating the imagery through various digital techniques to emulate and counterpoint the improvisational spirit of the performance.

Saturday, February 21 1:00pm

Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1976 | 15 min. | G 16mm

<–> (Back and Forth) dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1969 | 50 min. | G 16mm

“If Wavelength is metaphysics, Ear and Eye Control is philosophy and <–> will be physics.”—Michael Snow

Building on motifs that Snow had developed in both Wavelength and Standard Time (the latter of which will screen in the Fall programme)ßà is an exploration of interior space and the particulars of camera movement. Shooting in a university classroom in New Jersey, Snow rigged his tripod so that the camera could only pan within a certain range. The camera proceeds to pan from left to right, starting at a medium pace and then slowing down before speeding up; at its apex, the movement changes direction to tilt up and down at a similar pace, before slowing down to a final stop. Like Wavelength, the pan ignores the range of human activity in the room—a student reading, two students fighting, a janitor cleaning, a vernissage that includes Snow’s fellow artists Allan Kaprow and Max Neuhaus—instead utilizing speed to convert space into sheer motion.

“You aren’t within it. It isn’t within you. You’re beside it,” said Snow of <–>; by contrast, Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) flips the axis and literally pushes the viewer in. Set on a dolly, the camera slowly tracks across a fully set table until it reaches the far wall, the plates, utensils, food and drink all pushed along with it, creating a messily abstract sculpture. Both wryly humorous and subtly unsettling, Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) illustrates the potential violence innate to the film camera, an unstoppable force that captures and discards whatever is before it.

Thursday, March 12 6:30pm

La Région Centrale dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1971 | 180 min. 16mm

“La Région Centrale looks at landscape from a viewpoint it hasn’t been looked at before, so that it’s completely primordial— like seeing the world for the first time. It’s a whole movie caught up in a kind of movement that envelops the whole movie. In a movie, a scene is usually just a fraction of the event; a movement is just a fraction of it. In this movie, movement takes over the whole screen, the whole movie. It’s seeing things inside the cyclical movement of feeling or existence: the back-and-forth movement, the slow zoom movement. It’s being caught up in a whole force of vision.”—Manny Farber

While Wavelength is justly considered Snow’s masterpiece, La Région Centrale is his tour de force. Constructing an elaborate apparatus that enabled the camera to pan, tilt and rotate in every single direction, Snow and his collaborators brought the machine to a spot 100 kilometres north of Sept-Îles, Quebec. Over five days, Snow remotely directed the camera to shoot the imposingly barren landscape of the Canadian Shield in a kaleidoscopic variety of ways. With nothing else human or man-made visible apart from the shadow of the camera’s pedestal, La Région Centrale is a meditation on the purity of vision, landscape, and movement.

Thursday, April 23 6:30pm

Dripping Water dirs. Michael Snow & Joyce Wieland | Canada 1969 | 10 min. | 16mm

One Second in Montreal dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1969 | 26 min. | 16mm

See You Later – Au Revoir dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1990 | 17.5 min. 16mm

One of Snow’s central interests in his filmmaking is the passage of time, and these three films are some of his purest inquiries into this subject. Dripping Water, made with his then wife Joyce Wieland and using the sink in their New York loft, is comprised of a single shot of a faucet dripping on a small pile of dishes. The film’s soundtrack preceded the actual filming, and as a result the sink is not in sync, creating an anticipation between viewing and listening and amplifying the sense of waiting and watching. One Second in Montreal, made in the same year as Dripping Water, employs a similar minimalist approach. Repurposing thirty badly-printed off-set photographs that were given to him for a public sculpture competition, Snow presents each photo onscreen for a different period of time: the first fifteen shots get gradually slower, while the second fifteen rapidly speed up. These temporal variations, interacting with the nondescript nature of the photographic images, create a push/pull between duration and observation.

See You Later – Au Revoir is a single shot using a high-speed camera to elongate a simple action to a quarter of an hour. Snow performs the role of a businessman who gets up from his desk and walks past his secretary and out of the office. The simple ten- second action becomes a waking reverie as every detail becomes hyperreal, capable of being minutely examined as the unnaturally prolonged action unfolds.

Sunday, May 17 1:00pm

After a flurry of activity in his first decade as a filmmaker (eleven films in almost as many years), Michael Snow turned his attention back to his visual art and music for much of the next two decades. Following his last films of the 1970s, the epic Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen (which screens in the Fall programme) and Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) (which screened in the Spring), Snow would make only three films in the 1980s—the controversial Presents, the humorous rejoinder So Is This, and the underappreciated Seated Figures—but each one posed a provocative, enduring challenge to what we expect films to be and do. —Chris Kennedy

Side Seat Paintings Slides Sound Film dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1970 | 20 min. | G 16mm

A Casing Shelved dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1970 | 45 min. | G | 35mm slide with audio accompaniment

In 1970, Snow made two films that played off the standard promotional tool of the visual artist: the 35mm slide. While preparing a large retrospective of his work at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Snow became fascinated by the way in which slides and photos of his paintings became material in and of themselves. Further developing the idea of re-mediation that was central to his practice at the time, in Side Seat Paintings Slides Sound Film Snow stages an artist lecture, accompanied by a slide show featuring Snow’s paintings from 1955 to 1965, that he films from the worst seat in the house: the corner of the room. While the drastically acute angle transforms the slide into a trapezoid, Snow further distorts the experience by gradually slowing down and speeding up both the film and the soundtrack, changing the exposure of the image and the pitch of the sound. This audiovisual warping transforms the obscurely glimpsed projections of Snow’s paintings into new visual objects, and creates a completely different relationship between the viewer and the artist’s previous work.

A similar principle is at work in A Casing Shelved, which Snow has jokingly called his first 35mm film. (And so it is, although it consists of only a single 35mm slide projected from a slide carrousel.) It is also the first of Snow’s direct- address films, preceding So Is This by a dozen years and, perhaps, inspiring the use of narration in Hollis Frampton’s (nostalgia) (which was also voiced by Snow), made the year after. Snow’s tape-recorded narration guides us around a large shelving unit in his studio, filled with supplies and the loose ends of in- progress projects, describing the history of the objects that we see; as Federico Windhausen observes, “Snow’s narration attempts to direct our eyes toward specific portions of the image, as if spectatorial vision could function in a manner analogous to camera vision.”

Tuesday, June 16 6:30pm

Prelude dir. Michael Snow | Canada 2000 | 3.5 min. | 35mm

Presents dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1981 | 90 min. | 16mm

Presents, like many of its predecessors in Snow’s filmography, is essentially an investigation of camera movement, but from a more humorous and lyrical perspective. The first section is an extended sight gag: shot from a fixed camera, the scene focuses on a one- bedroom apartment where a woman is entertaining a visitor. As the pair move around the space, their wobbly movements and seemingly inexplicable attempts to maintain balance gradually reveal that the set itself is moving, being pulled back and forth by an off-screen truck. When the camera finally does move, it dollies onto the set and begins to smash into everything in front of it, in a hilarious extension of the visual violence previously explored in Breakfast (Table Top Dolly).

As the set falls away, the film suddenly transforms into an extended compendium of moving shots, all of them filmed with a handheld Bolex camera by Snow over the course of his international travels. For Snow to abandon the support of a tripod was a revelation, after a decade where his work had come to define the heady structuralist school of experimental film, with Brakhage’s tactile poesis at the opposite pole. But just as the eighties saw Brakhage experimenting with uncharacteristic techniques (e.g., occasionally adding soundtracks to his films), the diary of lush, gestural imagery in the second half of Presents undercuts the rigour and order we have come to expect of a “typical” Snow film; as Phillip Monk notes, “Snow pushes us into acceptance of present moments of vision, but the single drumbeat that coincides with each edit in this elegiac section announces each moment of life’s disappearance.”

Presents is preceded by Prelude, which was commissioned for the Toronto International Film Festival’s twenty-fifth anniversary. Six people are in a rush to get to a film screening, but Snow’s editing ensures that “everything in this film is either early or on time or late.”

Saturday, July 11 1:00pm

So Is This dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1982 | 43 min. 16mm

SSHTOORRTY dir. Michael Snow | Canada 2005 | 20 min. 35mm

“So Is This came as a surprise, as well as a response to the criticism Snow had received. With its formal simplicity and its humour—many saw it, not incorrectly, as an avant-garde comedy film—the film seems, at a deceiving first glance, to be slight, even a smart prank. But on reflection, which the film covertly solicits, So Is This is more than funny—it is a weave of sophisticated theoretical sarcasm.”—Bart Testa

Wavelength, <–> (Back and Forth), and La Région Centrale were Snow’s most critically acclaimed films, both because of their surprising new form and—paradoxically, given their almost purely formal concerns—their ability to be discussed in the political frameworks of the period. Certain prominent critics, influenced by French structuralist theory and British Marxism, embraced these films for what they saw as their materialist purity and critically- minded anti-illusionism. When Snow placed himself outside of that orthodoxy by returning to representation—most explicitly through the female nude that opens Presents—the backlash was violent. Coupled with this was a parallel attack from the opposite end of the political spectrum, in the form of the Ontario Censor Board’s attempts to ban sections of Rameau’s Nephew during a Snow retrospective at the Funnel Experimental Film Theatre. Snow responded to his critics of both ideological persuasions with So Is This. Consisting only of written text, displayed onscreen one word at a time, So Is This is described by Snow as a “communal reading” event. The film narrates its own existence, often taking us off on a tangent, circling back on itself, teasing the audience (and the Censor Board), or questioning its own being. It is perhaps Snow’s funniest film, a shaggy-dog story that gathers strength in the reading.

So Is This is followed by SSHTOORRTY, a more recent play on language (Farsi, in this case) and image—“a ‘painting’ about a painting in which Before and After become a Transparent Now,” according to Snow. The film is a short story superimposed upon itself and repeated multiple times, a lover’s spat and a ripped painting creating an endless loop of domestic hell.

Tuesday, August 11 6:30pm

Standard Time dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1967 | 8.5 min. | 16mm

Seated Figures dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1988 | 42 min. | 16mm

Puccini Conservato dir. Michael Snow | Canada 2008 | 10 min. | video

Although Seated Figures is characteristically confined by a specific placement of the camera—in this case, fixed to the rear of a pickup truck and aimed at the ground— the result is one of Snow’s most visually compelling films. As Snow drives the truck over all kinds of terrain—he has offhandedly described the film as a “history of roads”—we see a variety of textures flowing in front of the camera as this road movie unfolds: asphalt, gravel, dirt roads, sand, grass, flowers and shallow creeks. The imagery moves between abstraction and representation as different travelling speeds affect the legibility of the visuals, and as manmade surfaces give way to the beautifully variegated patterning of nature.

Seated Figures is bookended by two pieces made forty years apart. Described as a dry run for ßà , Standard Time is a back-and-forth pan across Snow’s apartment, a visual analogue for the radio-dial channel-surfing on the soundtrack. Commissioned to honour Puccini’s 150th birthday, the lighthearted Puccini Conservato—which observes Snow’s stereo while a track from La Bohème plays—takes a subtle, good- natured jab at recorded music. (When opera is canned, where do you look?)

Friday, September 25 6:30pm

Our year-long retrospective ends with three longer films that demonstrate one of Snow’s central working methods: isolating a point of focus and running it through every conceivable permutation. Whether exploring the possibilities of film sound, chemical processing, or digital manipulation, these works confront us with a gamut of ideas that illuminate, frustrate and tease.—Chris Kennedy

Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen

dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1974 | 270 min. | 16mm

At turns daunting, clever, perplexing and hilarious, Rameau’s Nephew is a true epic, in its length (four-and-a-half hours), its obsessive creation (Snow speaks of hundreds of notes and jottings that went towards the film’s development), and its ultimate execution (production went on for three years). In a series of twenty-five vignettes, Snow runs his cast—which includes such avant-garde luminaries as Nam June Paik, Joyce Wieland, Chantal Akerman, Jonas Mekas, Annette Michelson, Amy Taubin and P. Adams Sitney— through a series of explorations of sound and language, connecting the syntax of frame and sequence to that of syllable and sentence. With each episode focusing on a particular element of sound (a virtuosic drum solo on a kitchen sink, performers speaking backwards, offscreen voices describing action, an unidentified voice bouncing around a room), Rameau’s Nephew steadily accumulates into an encyclopedic satire worthy of its namesake, its sonic predilections both predicting and lampooning avant-garde cinema’s impending shift from structuralism’s critique of filmic illusionism to the theoretical discourse of the “New Talkie.”

Wednesday, September 30 6:30pm

Short Shave dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1965 | 4 min. | 16mm

To Lavoisier, Who Died in the Reign of Terror dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1991 | 53 min. 16mm

To Lavoisier originated in part from Snow’s attempt to deal with a stockpile of old film rolls that had accumulated over a quarter-century of his filmmaking. Shooting on a wide range of film stocks, Snow filmed a series of sequences of everyday life (breakfast, a bather, a friend reading, two people playing table tennis), often framed from above and accentuated by a slow zoom-in. He then passed the footage on to visual alchemist Carl Brown—who had developed a methodology of hand-processing outside of laboratory specifications and had previously worked with Snow on his own film Condensation of Sensation—who used a variety of techniques to “trouble” the images. The result transforms the quotidian into a dizzying downward spiral, the straightforward realism of the original images giving way to deranged photochemical abstraction via reticulation, bubbles, colour shifts and destroyed emulsion. The film is bookended by images of fire in a nod to its namesake, the eighteenth-century French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, who had used fire to articulate the law of transformation of energy wherein matter is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed.

To Lavoisier is preceded by Short Shave, an early short that predates Martin Scorsese’s The Big Shave by two years and is accurately described by Snow as “my worst film.”

Saturday, November 21 1:00pm

A to Z dir. Michael Snow | Canada 1956 | 7 min. | 16mm

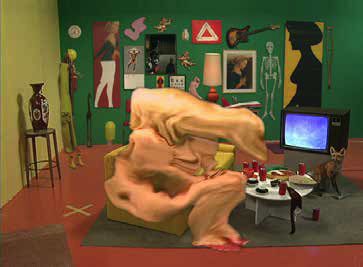

*Corpus Callosum dir. Michael Snow | Canada 2002 | 92 min. video

“*Corpus Callosum is resolutely ‘artificial’; it not only wants to convince, but also to be a perceived pictorial and musical phenomenon.” —Michael Snow

While Snow had utilized video in earlier films and installations, *Corpus Callosum was his first concerted attempt to explore the possibilities of digital technology. Set primarily in an office building overlooking downtown Toronto, *Corpus Callosum is comprised of a series of tracking shots across the office floor, where workers type away and two characters, a woman in a pink blouse and a man in red pants (who are not always played by the same actors), consistently take centre stage. This simple scenario soon becomes, in Snow’s words, “a tableaux of transformation, a tragi-comedy of the cinematic variables,” as Snow uses the Canadian-made software Houdini (which had previously been employed for such Hollywood features as Apollo 13 and Titanic) to playfully manipulate the images, stretching, inflating, electrocuting, and otherwise mutating the people onscreen in a gleeful dance of digital metamorphosis. In our current age of digital hyperrealism, *Corpus Callosum is a reminder of the delights of the patently artificial.

*Corpus Callosum is preceded by Snow’s first surviving film A to Z, an animation that Snow made off-hours during his employment at future Yellow Submarine director George Dunning’s animation studio.

Sunday, December 13 1:00pm

Snow’s Scene: Michael Snow in Context

Leading Michael Snow scholars Federico Windhausen and Malcolm Turvey discussed the artist’s lasting impact on the fields of film, sound, expanded cinema, and the visuals arts. This Higher Learning event was held on October 16, 2015 at TIFF Bell Lightbox.